Risk-taking is an important part of innovation for an economy and an important part of living an interesting life for individuals. Most innovations come not from the high ivory towers of research and “innovation labs” but from tinkerers and risk-takers trying to find better ways of doing things. Interesting lives don’t come from sitting in a sterile condominium in the DC beltway and working a safe job at a manilla-colored office — they come from making risky choices with the potential for high payoff.

What, then, is the level of individual wealth that is most highly correlated with calculated risk-taking? This is an important question for policy makers who concern themselves with basic incomes and welfare nets and is important for the individual who wants to introspect on the issue of taking healthy risks.

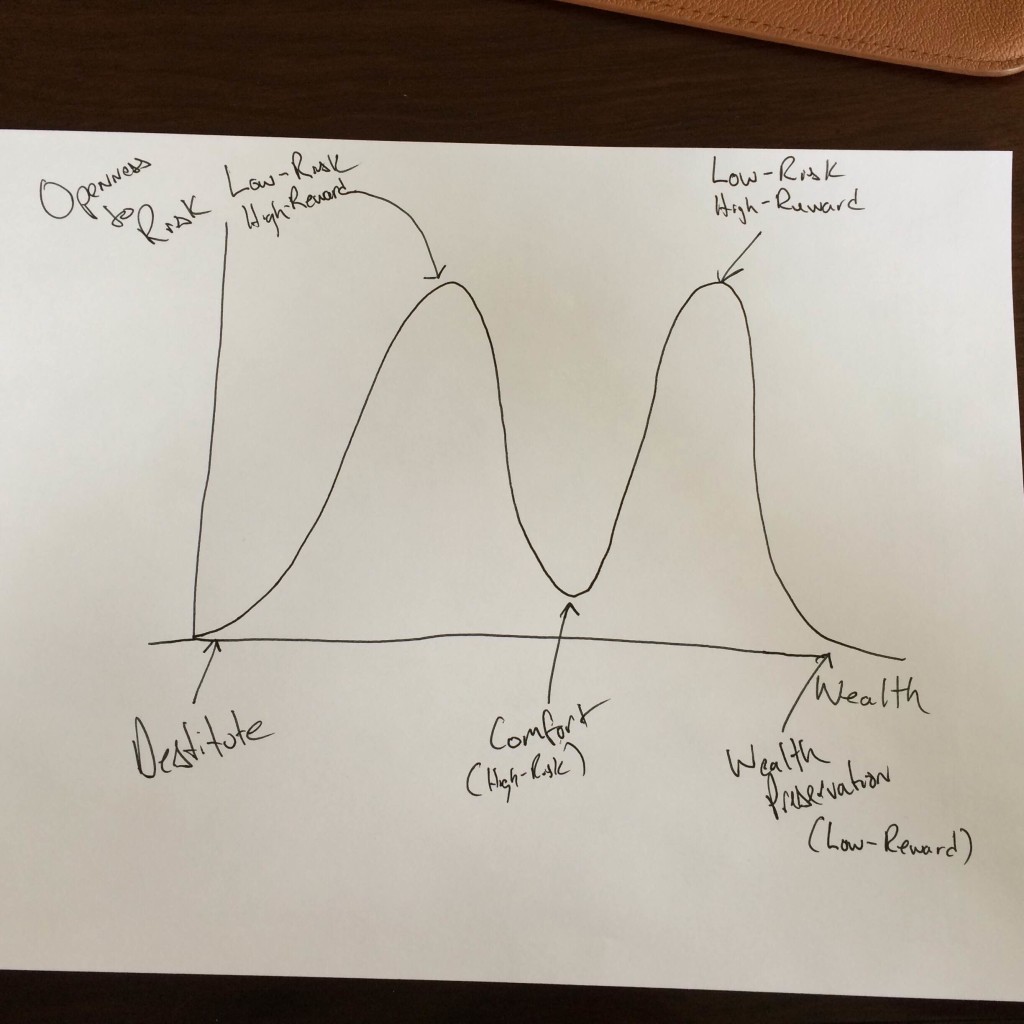

TL;DR — if you don’t want to read through my thought-process, I think risk-taking is correlated with wealth along a bimodal distribution (see below at the very bottom). The ultra-wealthy don’t really need more money from calculated risks and the ultra-poor don’t have time for it. The middle class has the lowest level of risk-taking outside of the tails because they have too much to lose and not enough to gain. The upper-lower class and lower-upper class have the highest levels for different reasons. ULC has enough capital to take small risks and has just enough security to not have to worry about basic needs. LUC has “f*ck you money” and can self-fund newer projects and can still focus on building, rather than preserving, wealth.

Risk-Taking as Calculated Investment, Not Speculation

Risk-taking here isn’t the cartoonish kind of jumping off a cliff and then finding a parachute. It’s not the uncalculated risk-taking of buying a ton of lottery tickets and not having anything at all left over for food. It’s the calculated risk-taking of successful entrepreneurs, creators, and traders. It includes both operations in the black and white markets — for example, drug dealing may be an appropriate calculated risk for an individual in the right circumstances. Similarly, money laundering could also be an appropriate calculated risk for the right individual.

Disclaimer for when speaking about aggregates: There are also a lot of other factors that play into the likelihood of an individual engaging in calculated risks, like upbringing (distance from calculated risk-takers), cultural norms (i.e., is failure considered death in the individual’s culture like it is in Japan? Or is it more recoverable like it is in most of the US?). I am not trying to say that individual wealth is the only determining factor of the likelihood that somebody will engage in calculated risk-taking. Rather, I am speculating on how wealth affects one’s perception of the rationality of engaging in calculated risks. Correlation is not causation and there will always be outliers.

Disclaimer when talking about risk: “Risk” means different things depending on where you are on the wealth timeline, too. When you are broke, spending $500 to start a design business may be perceived as extremely risky. When you are ultra-wealthy, spending $50 million on a new oil exploration company may be perceived as extremely risky but spending the $500 is seen as pocket change. This relativity of risk isn’t really that important here — I’m more interested in the general idea of thinking about risk and wealth than about the definition of risk.

There popular tropes on the Internet are that entrepreneurship and successful risk-taking looks like “jumping off a cliff and building a hang-glider on the way down.” To a certain extent, this is true. Many business ideas change multiple times as new opportunities arise (Raytheon, the weapons manufacturer, started as a refrigerator manufacturer). But the idea that success is a product of fly-by-your-seat risk taking is not the case. Most entrepreneurs I work with are decidedly risk-reducers (a sentiment echoed by Paul Graham of Y Combinator and Peter Diamandis of the XPRIZE). Their risk-taking is extremely calculated. They already know that they are taking a pretty big risk by going out on their own, so they try to reduce risks elsewhere. They tend to live fairly conservative lifestyles and invest their money in sound investments over which they have more control.

Nassim Taleb notes that we don’t make decisions based off of the probability that they will succeed, but instead based off of the payoff that they garner. People don’t drop out of college to build businesses based on the likelihood that the business will succeed (although that surely plays part of the calculation — I’m not going to invest time and money into Mail-order Nepalese Snowglobe startups), but more based on the size of the payoff should they succeed and the size of the loss should they fail. This is really useful for thinking about likelihood to engage in risky ventures below. We’re looking at payoff IF successful and loss IF failed — the calculation of what that IF is is largely left up to the context of the specific case.

Security & Risk: Basic Needs

Before you can engage in calculated risk-taking, you need to make sure you have your basics covered: food, shelter, a certain level of medical care, and security. Even if you had a propensity for risk-taking when destitute, actually getting these basics taken care of would take up so much of your time that you wouldn’t have much opportunity to engage in risky behavior.

After these are taken care of, though, you now have enough to get by but not enough to live comfortably. This allows people to concern themselves with creative risk-taking. Should you succeed at risk-taking at this stage, you don’t have much to lose if you fail and you have a lot to gain if you succeed.

A lot of immigrant entrepreneurs fall into this category. Starting in a new country — potentially displaced from their homeland — they have little to lose and a lot to gain by starting a business, and oftentimes its the only area that has barriers to entry low enough for them to succeed (Jews in mid-20th Century US are an example — they were excluded from highly-tracked careers and the institutions that acted as gatekeepers, so they opened up businesses instead — people don’t care about your religion as much if you can provide a good product or service. Capitalism is the great equalizer.).

Security & Risk: Comfort

At a certain point of wealth, you do have something to lose if your risk is miscalculated. Not only do you have something to lose, but the marginal benefit of every extra dollar brought your way actually starts to decline (~$70,000/year for most people). Unless you really score big and make millions, gaining an extra few dollars for hard work stops appearing to be worthwhile, especially if that work is really risky.

A certain level of material comfort brings with it fragility. Your likelihood to pay your mortgage is calculated according to the assumption that you’ll continue to make $X/month and $X + n over the coming years. Your ability to live in a certain region is predicated on the assumption that you’ll make a certain amount of money. For many people, especially those who choose not to save for retirement independently, retirement is an idea that is largely outside of their own hands and is controlled by the fragility of them having a job.

It becomes harder for people to take risks once they are comfortable. Comfort is paid for by assumptions and (oftentimes) debt and risky, high-payoff options come with lots of debt. If you have a hefty mortgage payment every month, it becomes harder to put $10,000 on your credit card for the new business you want to launch. If you have kids you have to feed, it becomes harder to take the pay cut when you are the only employee in your new venture.

Even though the potential payoff for success remains the same, the perceived loss in the event of failure has grown. It’s harder to go from comfortable to broke than it is from just-above-broke to broke.

There’s an odd thing that happens once somebody achieves something like middle-class comfort: people are less-likely to take risks with high payoffs. The perceived difficulty of the loss in event of failure outweighs the perceived payoff in the event of success. At this point, people would rather go work for Steve Jobs than risk some comfort at the chance to be him.

Does this mean that people stop engaging in risky, high-payoff ventures once they’ve achieved their conception of middle-class comfort? In other words, is affinity for risky ventures charted on an inverse exponential curve?

No. Not necessarily.

Risk & Payoff: F*Ck You Money

Once somebody has achieved a certain level of comfort, they perceive that there’s more to lose by risky ventures. But a level of wealth right beyond what is thought of as “middle-class comfort” can be described as “f*ck you money.” The idea of “f*ck you money” (FYM) has been around for a few decades and has different interpretations depending on how you view money. For the context here, FYM can simply be thought of as a level of wealth at which you are not dependent on other people’s money (OPM) for support.

This can mean quitting your job because you don’t need the monthly paycheck and can support yourself or it can mean seed-funding your next venture. Those at “middle-class comfort” are usually dependent on OPM or a small number of immediate clients, making independence and risky ventures harder. Achieving upper-middle class, lower-upper class status is rare for those who don’t work in a handful of fields, many of whom are self-made entrepreneurs who don’t need to be dependent on OPM anyway.

These people have achieved a level of wealth where they are less-likely to worry about the bottom falling out — they probably have one already-secure venture generating income for them or a series of “safe” investments like IRAs and bonds. Even if their new risky venture fails, the bottom probably isn’t going to fall out for them.

The hidden element here, too, is that people at this level of wealth are more likely to already be independent and have already tried out risky ventures (how they got independent in the first place). Risky ventures feel less risky if you’ve already succeeded at one. This is why you’ll find that a lot of venture capitalists (VC is a notoriously risky field) are former founders who cashed out on one business already. A doctor is much less likely to have FYM despite earning a high salary — he’s probably more dependent on his salary to pay off the mortgage, loans, and taxes than the cashed-out entrepreneur (also why it is important to note that the X axis we are using is “wealth” and not “salary” or “income” — people with a lot of outstanding debt but high incomes can have relatively low wealth despite their status).

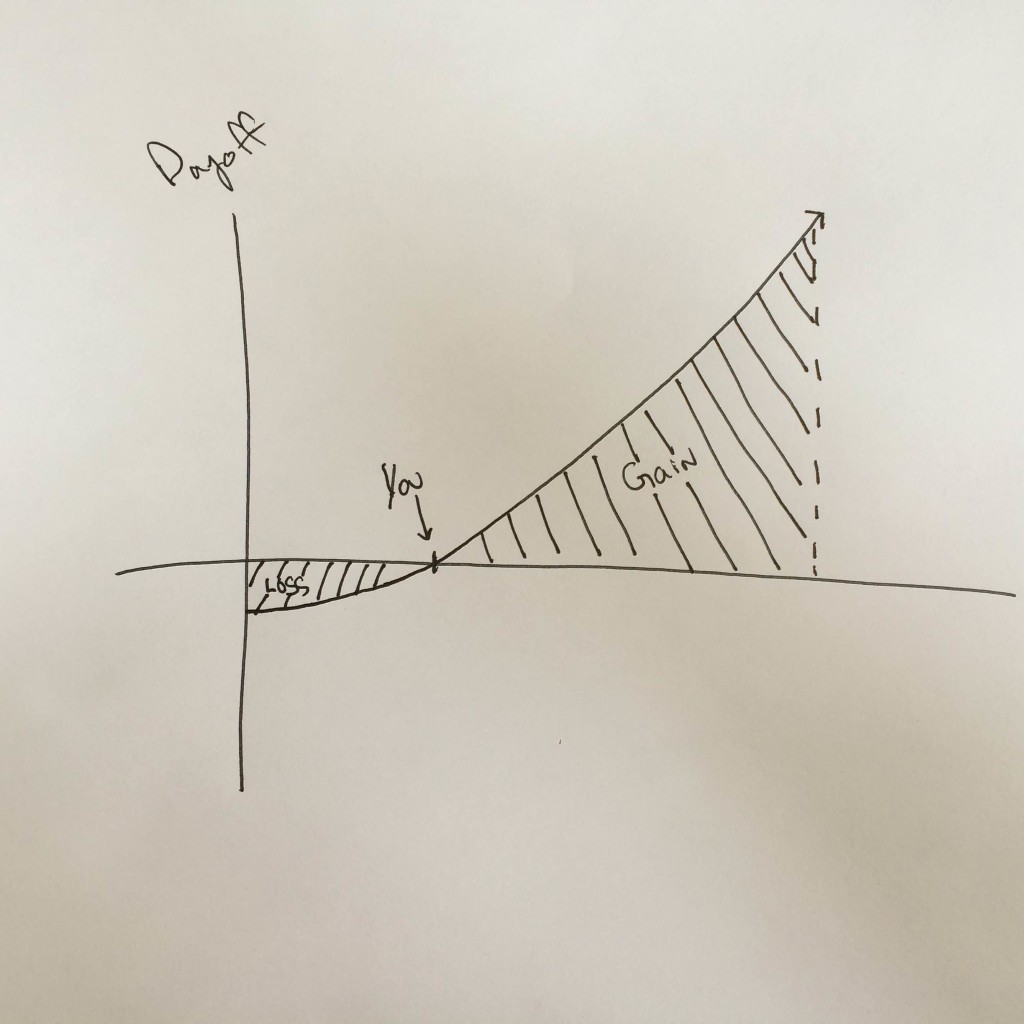

People with FYM have the ability to keep building wealth. They are “wealthy” by popular terms, but they aren’t necessarily “estate in the Hamptons and three private jets” wealthy. They probably lead modest lives and live in upper-middle class neighborhoods (see The Millionaire Next Door for an outline of these people). Their perception of loss and gains is illustrated by Figure A.

Ultra-wealthy: Preservation, Not Growth

“Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations.”

This is a popular saying about the difficulty to maintain wealth over generations. You can find plenty of ruin porn articles on the Internet about some grandson of a wealthy real estate or oil mogul who blows all the money on useless stuff or pure speculation. In the world of estate managing, preserving the wealth of the ultra-wealthy is harder and more important than building that wealth.

Like the middle class, the Ultra-Wealthy (net worth ~$50MM+) perceive more to lose on risky ventures than what they can gain. Unlike the middle class, the lack of perceived growth is actually because they really can’t go much bigger. With the exception of seed-funding a space-exploration company, these individuals and families can afford most of the material comfort that individuals search for in life. The marginal return of each additional dollar really is less important to them.

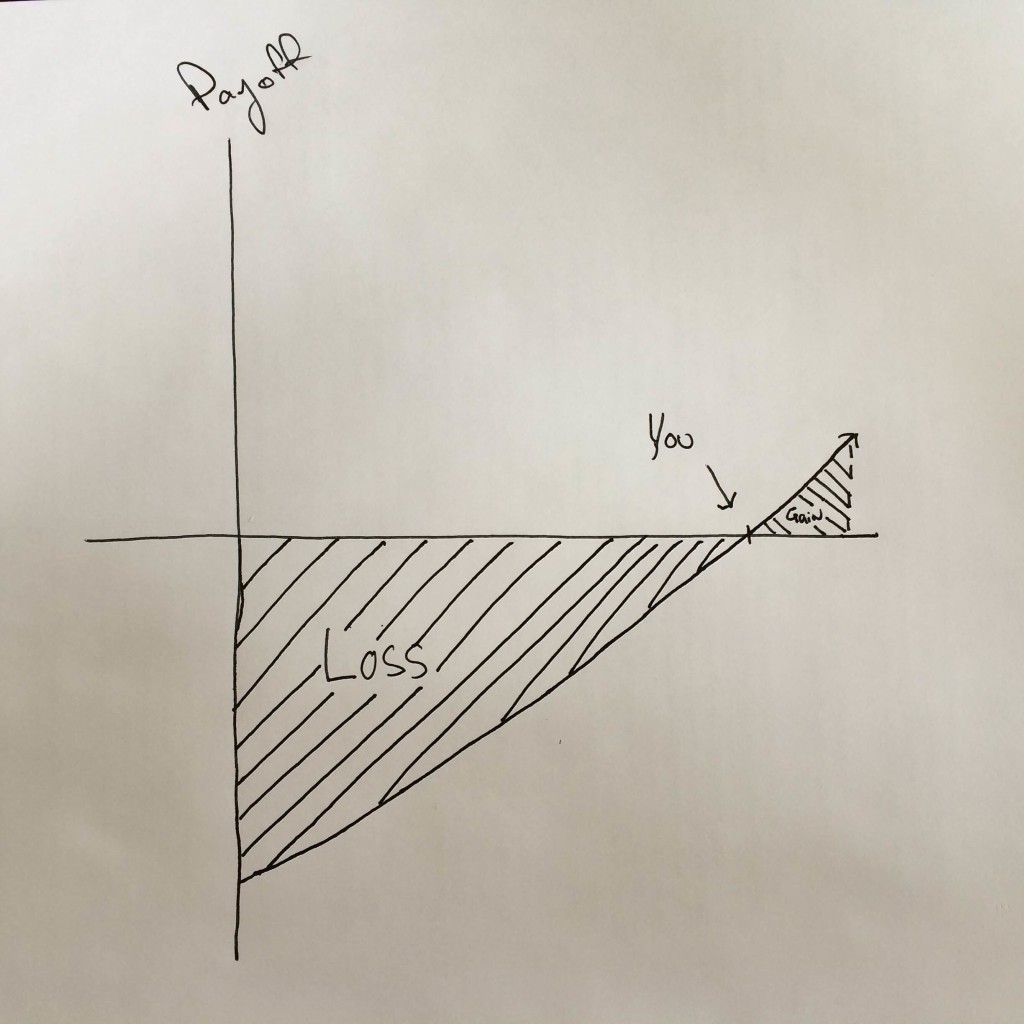

For these individuals, emphasis usually falls on how to set up the estate so that children and grandchildren can preserve the wealth intergenerationally. For them, Figure B illustrates their perception of risky ventures.

Wealth and Risk: A Bimodal Distribution

Understanding the dynamics at play on both tail ends of the spectrum (destitute and ultra-wealthy) lets us rule out any kind of normal distribution or exponential curves. The perception of risk at the point of mid-wealth rules out a normal distribution.

The relationship between wealth and openness to risky, high-payoff ventures is a bimodal distribution.

Having a certain level of wealth — what politicians and pundits paint as “the middle class” (a phrase I hate because most people perceive themselves as being middle class, regardless of where their wealth really lies) — is actually less conducive to fostering risky ventures and the opportunities they generate than having less or more than that wealth. This explains why you’ll find people with comfortable, mid-wealth, good-paying jobs who wish they could go back and take the riskier path when they were younger and had fewer resources to actually start on that path.

If you find yourself chewing at the bit to jump on a risky venture but worried that it may be better to take the safer, more established route and then change ships once you’ve gained more resources, consider that the opposite may be better. It can be really hard to move off the hedonic treadmill once you start running.

I pull heavily on Nassim Taleb’s ideas from Antifragile for this piece. If the idea of mid-wealth actually fragilizing you to risk intrigues you, I recommend checking out the book.