One of the most popular tropes among career advisors, guidance counselors, school officials, and college recruiters today is that going to college is an investment. As more and more options for work experience and education outside of the higher education cartel crop up, those pushing the college option on young people are forced to fall back on telling the young that, though it may look costly now, it will pay off in the future. Like their Housing Crisis predecessors, they urge young people to take on the seemingly-unimaginable cost with some statistics and graphics showing that, in the recent past, a college degree pays for itself over a lifetime.

It’s time that we admit that this isn’t the case.

The “it’s an investment!” strategy of sending young people to universities is one of the last options available to those urging people to take on this stodgy, quickly-outdated, and inefficient way to build the life that they want. If anything, this idea that it will pay off in the long run is mere speculation, not investment.

Let’s take a look at what I mean.

In the investing world, making speculations is contrasted with making intelligent investments. Investments tend to have a safety of principle and an adequate minimum return. A speculation is something that doesn’t provide this.

All investment requires an element of risk — this doesn’t mean that a speculation is simply a risky investment. It’s an investment that doesn’t give you reason to believe that you’ll actually preserve your principle (the money you initially put in) and give you a return (get you the money that you want).

Stop citing those roi studies

Here’s where the college recruiter/advocate interjects, telling me that on my own definition, college is a great investment. “Just look at the ROI rankings put out by Payscale and Forbes and US News! They say that the data clearly point to a positive ROI!”

But this is misleading.

This assumes that the graduate is a mere lottery ticket and the aggregate of all the attendees at their school. This includes comparing a petroleum engineer to a philosophy major to a Gender Studies major to a business student. At best, this just tells us more about the selection bias in these schools.

(I have written more on problems with these ROI reports and their inability to parse out the selection bias inherent in higher-ranking schools here. In short, these schools take people who would probably be successful anyways and then claim credit for their success. It’s a great recruiting and fundraising tactic, really.)

To rely on this data is to be too quick to declare that the degree is an investment with a minimum ROI. A better study would be to take a large sample who got into the same university (status really doesn’t matter), with the same SAT scores and aptitudes, and follow them over the course of their careers as half drop out and half completes the degree. You would also have to control for elements like where they moved, family structure, background, and more.

If this sounds ridiculous, it’s because it is. There are so many other factors that go into determining the success or failure of a young person over the span of their careers that to turn it on one issue is ludicrous.

But let us assume that the college factor is the overriding, major contributing factor to one’s career. Maybe ROI isn’t the best factor. What about attempting to get the job?

If job is what matters, the Degree is probably speculation

Most young people go to college to get a job, not to get an education or to open themselves up to new and interesting viewpoints. If you think this sounds cynical, follow a simple thought experiment next time you meet a group of college students.

Ask them if they would still pay whatever they (or somebody else) are paying for their degree if, when they graduated, they stood no better chance at employment (or even a worse chance!) than when they started. If they’re being honest with you, most would tell you no, they would not still go.

While a good job should be related to financial gains, it’s not always a direct correlation, so maybe a better determiner of return is whether or not graduates land in jobs that require degrees.

If that’s the case, then the data are sketchy.

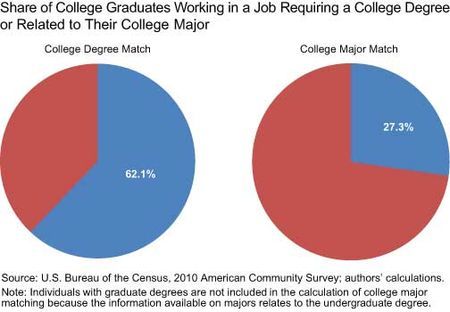

In 2013, only 27% of college grads landed a job in a field related to their major. But around 60% landed a job requiring a degree.

You could attribute this percentage to a slow recovery, assuming it would increase year-over-year as job prospects improve across the economy as a whole.

In 2014, only 51% of college graduates landed jobs that required degrees, down nearly 10% from the year before.

It’s too early to really say what 2015 yields for college graduates, but this trend isn’t surprising to me. I spend most of my time talking to employers and scouring careers sites, looking for trends and trying to get ahead of the pack so that I can provide the best education-training experience possible. One of the major trends I noticed, even among traditionally stodgy industries like accounting, consulting, and advertising, is that employers care more about what you can do than about what you claim than ever before. The rise in “degree or equivalent work experience” is stronger than ever. The rise of the Internet and of personal digital brands makes it much easier for an employer to verify claims about whether or not a person knows something. This means more companies can move away from the credential requirement as a filtering mechanism and instead switch over to simply googling a candidate, looking up their LinkedIn, or being provided with a professional portfolio.

Of course, if your mission is to land a job in an industry protected by legal degree requirements, like accounting, medicine, or law, then the undergraduate degree is a great investment. If your goal is to land a job in general, then you’re probably speculating.

You’re not a retirement Account

If you want something safe that will yield a decent ROI in the investment world, something like a Vanguard or a Fidelity ETF account is what most people use. It’s highly diversified between different kinds of stocks and with some federal and municipal bonds. It won’t make you rich, but it should give you more money than with which you started.

You’re not a retirement account, though.

You can’t diversify yourself between a half-dozen different options in career, education, schooling, credentialing, and skills.

In fact, the pursuit of college, especially elite college, dilutes your ability to valuably invest in yourself.

“By the time a student gets to college, he’s spent a decade curating a bewilderingly diverse resume to prepare for a completely unknowable future. Come what may, he’s ready–for nothing in particular.”

— Peter Thiel, Zero to One

While you should be focusing on the things that you know and that you know well, the things that you can do well, and the things that you enjoy the most, you spend your most formative years diversifying your skills and experience portfolio to the point that you can’t yield all that much more than if you just stayed home and didn’t really do anything.

This is how investing for a big payoff works, too. Warren Buffett invests in things that he knows and things that he knows well. All of the best investors make a smaller number of higher-knowledge investments. Thiel urges against diversification if you want to really excel, both in investing and in yourself.

Know what you want

The problem with education and schooling is the same as the problem with too many wannabe investors today — people don’t know what they want. They go in with a general lofty goal like, “get a good job,” or “buy a house,” or “get rich,” without putting actual parameters on these goals. What is a good job? Why do you want the house? How rich? When? Why? How?

It’s a continuation of what Thiel calls “indefinite optimism.” People work towards general goals and general needs for “better,” but don’t actually know what paths make up this “better.”

In education and schooling this means we are just constantly moving from one goalpost to the next, rarely asking what the end goal is and why we are following that path. We want to go to a good high school and get good grades so that we can get into a good college so that we can go to a good graduate school so that we can land a good job so that we can…what?

“Indefinite attitudes to the future explain what’s most dysfunctional in our world today. Process trumps substance: when people lack concrete plans to carry out, they use formal rules to assemble a portfolio of various options. This describes Americans today. In middle school, we’re encouraged to start hoarding “extracurricular activities.” In high school, ambitious students compete even harder to appear omnicompetent. By the time a student gets to college, he’s spent a decade curating a bewilderingly diverse résumé to prepare for a completely unknowable future. Come what may, he’s ready—for nothing in particular.”

— Peter Thiel, Zero to One

Many students attend college to get a good job without asking why they are going in the first place, what kind of job they want to have, what kind of life they want to live, and what they want to make of themselves. They think in general terms. This applies to their spending and saving habits once they get out of college. Why should they save now? The money has always been there for them, they can get loans to go to college, buy a house, get a car, etc.

This leads people to speculate not only with their educations but with their careers, too. Speculating with your career leads to speculating with your family life, your hobbies, your friends, and generally leads to an indefinite, unstable future.

Consider the alternatives

When you don’t know what you want from your life or career, going to college quickly jumps from being an investment to being a speculation. Even good colleges can’t make up for that fact.

Most studies and talks of whether or not degrees are worth the time and money assume the alternative is sitting around being a stoner on the couch and eating doritos. This doesn’t have to be the case, though. If you spend this time constructively, building your human and social capital, engaging with ideas and actually seeking an education (contra just a credential), then you can come out making much more with this time than your peers.

For more high-achieving young people today, knowing what they want and building a path to get there will prove to be a much stronger investment than blowing four years on an indefinite shot at “a good job.”

Contact me if you are interested in discussing some options for spending this time more constructively.