This is a guest post by Professor Jason Brennan, the Robert J. and Elizabeth Flanagan Family Professor of Strategy, Economics, Ethics, and Public Policy at the McDonough School of Business and Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University.

He’s also the author of several forthcoming books, including In Defense of Openness, with Bas van der Vossen.

I’ve interviewed Professor Brennan before on how he maintains a prolific output that helps him succeed in academia (to give you an idea, he sent me this article just a few hours after I emailed him requesting it, complete with citations). I asked Professor Brennan to put this together because he’s a great example of how somebody can be successful in academia and he doesn’t sugarcoat what it takes.

Should I Get a PhD and Become a Professor?

TL;DR VERSION: Academia is glorious, but the odds of getting any long-term faculty job, let alone a glorious one, are low. Know the risks and plan accordingly.

Zak recently wrote about the pros and cons of getting a master’s degree.

What if you love the life of the mind and are considering being a college professor?

Here’s some candid advice and things to consider. Also, presume this advice applies only to the US and Canada. Academia in other countries can be quite different (and in most countries, quite a bit worse).

To start, here’s what you do when you get a Ph.D.: http://matt.might.net/articles/phd-school-in-pictures/

Does that sound attractive to you? If not, stop here. If yes, keep reading.

A PhD is a professional degree, like an MBA or a JD.

It’s designed, rather poorly, to make you an academic. Some people—certain engineers, corporate scientists, would-be school superintendents—get doctorates for professional advancement. Econ PhDs can get great jobs in banks, investment firms, or in government. But in general, the purpose of a PhD program is to create professors.

So, except in special cases, the basic advice is that you should get a PhD only if you want to be a professor. Do you? I’ll discuss what that’s like shortly.

Most PhD programs provides very poor preparation for life as a professor.

They provide lots of instruction about how to produce original research and how to publish that research. They provide almost no guidance or mentoring on how to teach undergraduates, though they will throw you in a classroom and let you practice.

PhD programs train you for doing research, but in reality, the overwhelming majority of professors in the United States do very little research and instead spend most of their time teaching. They are more like glorified high-school teachers than scientists or researchers.

The HERI surveys conducted by UCLA indicate that a minority of faculty produce the majority of research [1]. 28% of faculty say they have published nothing in the past two years, while another 31% say they’ve published only 1 or 2 pieces. About 60% percent of faculty average less than 1 publication a year.

Even at research universities, most professors spend most of their time teaching: A 2003 survey by the U.S. Department of Education finds the average research university professor spends roughly 24 hours per week on teaching-related activities. [2] At non-research universities, faculty spend more than 2/3rds of their time on teaching-related activities. [3] Only at the most elite, research-oriented places do most professors focus on research over teaching. E.g., of the 2000 hours I work/year, I spend maybe 1500 on writing. But I have an unusual job.

What Professor Jobs Are Like

Academic jobs are not all the same thing. What the job is like depends on both A) where you work; and B) what kind of gig you get.

I won’t belabor this, but you probably know there is tremendous variation in higher ed. Working at Bunker Hill Community College is different from working at UMass, Boston, which is different from working at UMass, Amherst, which is different from working at Amherst College, which is different from working at Harvard.

At community colleges, you’ll have few or zero research expectations. You’ll teach largely remedial classes or introductory courses for students hoping to transfer to a four-year college.

At lower ranked liberal arts and state research universities, you’ll have mild research expectations, and spend much of your time teaching lower quality undergraduates (though you’ll see tremendous variation in students’ skills and preparedness).

At more elite liberal arts colleges, you’ll do lots of teaching and service, you’ll have good students, and you’ll be expected to publish at a high level regularly.

At an elite research university, you’ll in general spend most of your time doing research. You’ll be expected to publish continuously in elite journals or with elite book publishers. Teaching will be a distant second.

What the job requires also depends on what kind of job you get. Even Harvard has faculty who teach full-time and never do research. While there are lots of kinds of full-time academic jobs, we can break them down into two categories: tenure-track and non-tenure-track.

Tenure-track: Tenure-track jobs are the gold standard academic gig. You begin as an assistant professor. After six to eight years, you undergo an external review, in which senior peers from other universities examine your research, your teaching, and your service to the profession and your university. If you fail the review, you get fired. If you pass, you get tenure—which means you can be fired only for gross incompetence or because the university faces severe financial trouble—and promoted to associate professor. If you keep up the good work, you can get promoted to full professor, and from there, you might be given an “endowed chair” or “university professorship”—a kind of fancier, higher status gig that comes with perks.

The weight of these three things (research, teaching, and service) depends on your institution. At Yale or Penn, promotion decisions are almost entirely based on research, though people will put on a pretense that teaching and service matter. On others, e.g., a small liberal arts college, promotion is based almost entirely on teaching and service.

Tenure-track faculty generally receive the best pay, the best perks, the highest status, and the most job security.

Non-Tenure-Track: However, most full-time faculty are not on the tenure-track. Here are some job titles you may have seen: instructor, lecturer, senior lecturer, distinguished lecturer, professor of the practice, assistant teaching professor, associate teaching professor, teaching professor. These gigs come with lower pay, lower status, and lower security. Such faculty often get rolling long-term contracts, but it’s easier to fire them than to fire the tenure-track faculty. They are expected to do lots of teaching and service, but no research. There are also non-tenure-track research professorships, often with titles like “clinical professors” or “research professors”. These gigs also usually have lower pay, status, and security than tenure-track jobs, but are focused entirely on research to the exclusion of teaching.

How Much Teaching?

The kind of teaching varies, too. A small college with only three faculty in a department might require you to teach six distinct classes, only one of which is in your area of expertise. At research universities, faculty might get to teach graduate seminars focusing on cutting edge topics, including their own work.

What About Pay?

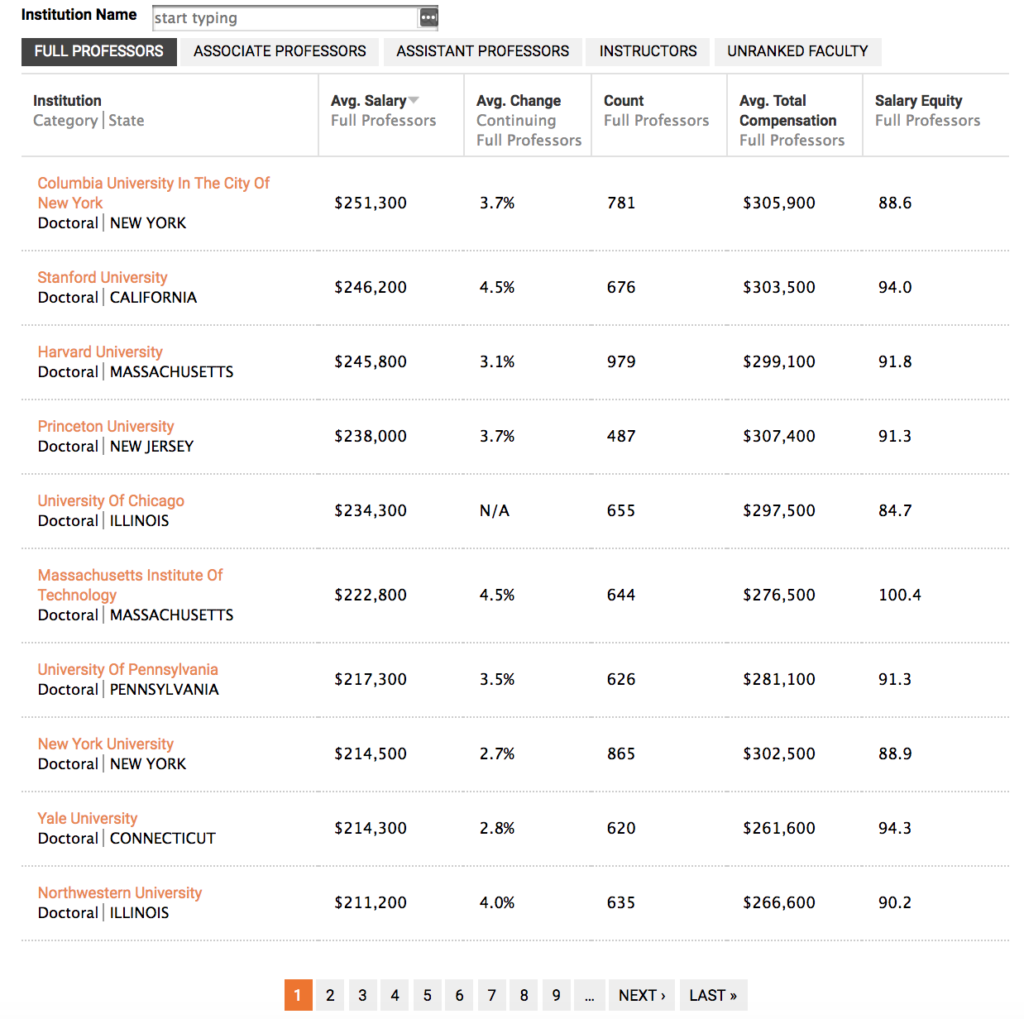

Take a look at the survey data here: https://www.insidehighered.com/aaup-compensation-survey

In 2017, across all four-year colleges and universities in the USA, full professors average $104,280 associate professors make $81,274, and assistant professors make $70,791. [4] At private and doctoral-granting universities, professors make significantly more. In contrast, in 2015, the median household (rather than individual) income in the US was about $59,039, while mean household income was about $72,000. [5] Even relatively badly paid professors make more money than most other people in developed countries. Some professors cry poor, but that’s usually for self-serving reasons.

Those are US national averages. But averages can be misleading or uninformative. To illustrate, I entered grad school (at the #8 program in philosophy) with a class of four in fall 2002. All four of us graduated and have full-time academic jobs. Based on public data, I’d estimate our mean academic salary today is $125,000. But two make much less than that, while I make more than twice that. My nominal salary is six times the nominal salary of the lowest paid of us.

“We make $125K/year on average” tells you little.

Pay depends on 1) how rich the college or university is, 2) which field the professor works in, and 3) how famous or important a particular professor is. To illustrate:

- Harvard University, with its $38-billion endowment, [6] pays full professors on average about $220,000 and assistant professors about $122,000. [7] In contrast, Tusculum College in Tennessee, with its $16-million endowment, pays full professors less than $43,000 a year. [8]

- Brand new tenure-track assistant professors in business, computer science, engineering, and law, tend to make about $30K more to start on average than professors in history, psychology, or English. [9] Business, law, and medical profs can easily make more than twice what their colleagues in the social sciences or humanities make.

- Universities compete to hire and retain star professors. Top professors make far more than others. Some star medical and business school faculty receive multi-million dollar salaries. [10] In general, the more and better you publish, the more you make. Even star humanities professors at elite schools can make well over $300,000 a year in their base salaries, plus also secure significant honoraria, speaking fees, and book royalties. Harvard pays John Bates Clark Medal-winning economist Roland Fryer over $600,000 a year. [11]

- Book royalties, speaking fees, and so on, can significantly add to your income. Some professors get $500 to give a talk; others get $25,000. Some make $500 lifetime from a book, while others make tens of thousands or, in rare cases, millions.

Professors on average earn more money than most people; a few earn much more than average.

Being a Professor Can Be Glorious or It Can Suck

I have an awesome job. I get paid to play with ideas. If you have a passion for ideas, there are fewer jobs better than being a college professor. I have a remarkable amount of freedom and autonomy in determining how I spend my days. I spend most of my time every week thinking and writing about whatever I happen to find interesting. So long as I publish it in an impressive place, Georgetown gives me a big raise and a pat on the back. I teach at most three classes a year, and get nearly complete autonomy in determining what goes in my classes. My students are smart, driven, and conscientious. I am expected to do only small amounts of administrative or service work, and most of the service work I do is intrinsically rewarding rather than time-wasting bullshit.

But I have one of the most plum jobs in the academy. Most people who work in academia have much less freedom than I do. They spend much more of their time doing administrative work, often work that is grueling and pointless. They teach more classes than I do to lower quality students who don’t care about learning for learning’s sake and who don’t find the material interesting. They rarely teach courses on topics that interest them. And they do this for much less money.

On the other hand, many faculty would hate my job and would prefer more teaching and service-oriented gigs. They get lower-quality students, but because of that, they might have more of a chance of making a difference, of actually improving the students’ skills. They might be happy to be free of the constant and severe pressure to publish which I face, and instead be glad to have a predictable schedule of teaching and service without having to worry about what the next book will be.

The Schmidtz Test

My mentor, David Schmidtz, advised students to ask themselves, “What’s the bare minimum/lowest pay/status/quality academic job I’d be happy with?” Ask yourself that.

If you answer is, “I’d be happy to teach third-tier undergrads at St. Anselm College for $68K/year, and delighted with anything ‘better’ that that,” maybe you should go to grad school. (But see below.)

If your answer is, “I’d be okay tenure-track at any of the Ivies and their peers, plus Berkeley and Michigan,” you probably shouldn’t go, because you almost certainly won’t end up with a job like that.

What Are My Chances?

So, now you’ve got a taste for what being a professor is like. What does it take to become one?

Once again, there is tremendous variation among different fields. But the numbers roughly work out as follows: Of every 100 people who start a PhD program, 50 will quit or fail out. Roughly 10 will ever get a tenure-track job. [12]

Out of all full-time tenure-track jobs, roughly 1 out of 10 is research-focused, while the other 9 are teaching and service-focused. Colleges today have roughly a 1:1 tenure-track to non-tenure-track but full-time ratio. So, basically 1 out of 20 full-time academic faculty jobs is research-focused (with the high pay and status that come with it) while the other 19 are teaching a service-focused.

In short, for every 100 people who start PhD programs this year, maybe 1 will end up becoming a full-time academic researcher. 20 or so will become full-time teachers with varying researcher expectations.

How Do I Beat the Odds?

To get a full-time job, period, let alone one of the fancier ones, you should generally:

- Not get a degree in art history, English, comparative literature, or most of the humanities fields. The ratio of graduating PhDs to jobs keeps getting higher every year, and there a bunch of underemployed PhDs from recent years competing for the new jobs.

- Go to the highest ranked graduate program you can get into. Generally speaking, the top 10 or so grad programs do an excellent job placing their students. As you move down the rankings, your chances of getting any full-time academic job, let alone a cushy one, approach zero.

- As a graduate student, publish as much as possible in highly-ranked journals. There are a huge number of applicants competing for a small number of spots. You have to stand out. What it takes to get a tenure-track job today is greater than what it took to get tenure three decades ago.

- Get a famous dissertation supervisor who has lots of connections.

How Do I Publish?

See here: http://dailynous.com/2016/11/10/productive-publishing-guest-post-jason-brennan/

Pay attention to some of the responses from other academics. You might not like having such people as colleagues.

How Much Does It Cost?

Any decent PhD program will waive tuition and offer you a living stipend of between $15-30K a year (Again, exception: Certain engineering or science programs aimed at corporate professionals). The living stipend may require you to work as a teaching or research assistant. Teaching assistants supposedly require 20 hours of work per week from you, but in reality, if you are fast at grading and a good time manager, it’s more like 5 hours on a typical week and maybe 10 on a bad week. You should prep for your discussion sections during your professors’ lectures.

If a PhD program asks you to pay tuition or if it fails to offer you a living stipend, you should not enroll. Period. That’s a very strong sign either that the program sucks or that you are not good enough to make it. Sorry.

Never take on debt to get a PhD. The chances of failure are too high. The likelihood that you’ll get a job with a sufficiently high salary to offset the debt is too high. Don’t do it.

Believing you are the exception to these two rules is unexceptional.

Free tuition and a living stipend doesn’t make the PhD free. You are giving up 5-10 years of the higher salary, 401(k) contributions, work experience, and so on you would have had outside of academia. Many academics don’t get their first full-time academic job until their late 30s.

(Zak’s note: See my post on opportunity cost here.)

You can easily find yourself in your mid to late thirties still a graduate student, making a measly $20K a year living stipend, with no real job, no savings, a crappy old car or no car, and a tiny, lousy apartment, while your friends own houses, cars, and make six figures. Think about the opportunity cost. You forgo many opportunities to study for a Ph.D., and there’s little chance of getting any professorship at the end, let alone a good professorship.

What Happens to PhDs Who Fail to Get Full-Time Faculty Jobs?

Some become adjuncts—they work part-time, on a pay-per-course basis teaching at various colleges. Pay-per-course is around $3100, but it can be much lower or higher. Most adjuncts, however, do not have a PhD. [13]

Others get temporary but better full-time jobs as post-doctoral fellows or, less desirably, visiting assistant professors. They might string together a few jobs like that for a few years while they continue to compete for the better jobs.

The good news is that there are good exit options. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate in the United States, in 2015, for master’s degree holders was 2.4%, and for Ph.D. holders was 1.7%. [14] Empirical work shows that most PhDs, after they quit trying to secure permanent college faculty positions, find employment elsewhere, for instance as academic administrators, as high school teachers, in NGOs, in government, or in private business. [15] Most people who get a PhD do not end up securing a long-term academic position, and yet the majority do find full-time employment elsewhere. [16]

I like reading and discussing economics or political philosophy. It’s my hobby. Should I get a PhD?

You can do all these things without getting a Ph.D.

You can read and discuss economics while holding down a job as an insurance agent, a lawyer, or a consultant. You might be able to maintain your hobby while making a lot more money.

I’m the smartest philosophy major at my college, in fact, the smartest they’ve ever had. Should I go to grad school?

Probably not.

Graduate programs get hundreds of applications for a few spots. Pretty much all of the applicants were the smartest undergraduate majors in their colleges.

How hard is it to get in?

At a good graduate program, the acceptance rate will be under 10%, perhaps much lower than that.

What do you do in grad school?

You take classes for 2-3 years in a wide range of subfields. You’ll write 12-16 30-page seminar papers. You’ll read thousands of pages of material.

After that, you’ll usually take some sort of exam to show you have expertise in one subfield and a broad range of knowledge in other subfields. If you fail that, you’ll get kicked out.

If you succeed, you’ll devise an original research project. You then take an exam – a “prospectus defense” – to determine whether your project is even worth pursuing. This is a real exam, and repeated failing = getting kicked out, usually with a master’s degree as a consolation prize. (I’ve seen this happen. A few years ago, my colleagues and I failed a grad student who couldn’t write a coherent proposal for a dissertation.)

If you pass the prospectus defense, you then write a dissertation. Once again, you take an exam when you’re done. If you fail, you get kicked out, with a master’s degree as a consolation prize. If you succeed, you get the Ph.D. The whole process should take 5 years–maybe less if you do econ–but most people tend to take 6 or 7 years, and in fields like history, they take even more.

If You Find Grad School Hard, You Should Quit

Grad school is incredibly easy compared to being an assistant professor.

(I’ll probably get some angry emails about this, but it’s generally true.)

In grad school, leading faculty tell you what to read. You have few responsibilities other than reading, writing a few papers, and work as an assistant tp a professor in teaching a few hours a week. Your professors write the syllabi, while you just lead discussion sections. Your professors will tell you what you need to read and will issue-spot for you—they’ll tell you where the action is on some debate and how to make a contribution.

When you become a professor, in general, you lose all that. No one tells you what to read or where the action is. Rather than having to assist a few hours in someone else’s course, you have to design, prepare, and deliver multiple courses of your own. Sure, you’ll get better as you practice, but if grad school is overwhelming, the job is usually much worse.

That said, graduate school is a glorious time, and there are worse ways to spend your life. Many intellectuals would be happy to pursue the degree just for the sake of having the graduate school experience.

Citations

[1] https://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/HERI-FAC2014-monograph-expanded.pdf, p. 30.

[2] IPEDS Table 315.3. Note: these findings were also consistent with an earlier 1994 AAUP study, itself based on earlier Department of Education data going back to 1987. See Rosenthal 1994. Similar attestations of faculty time allocation may be found in the 2010-11 Higher Education Research Institute survey, particulary pp. 26-27. http://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/HERI-FAC2011-Monograph-Expanded.pdf The consistency of these studies suggest that full time faculty teaching obligations have remained relatively stable for several decades.

[3] IPEDS 315.30. See also HERI 2010, pp. 26-27, which suggests a similar increase in teaching-related time allocation for faculty at 4 year colleges when compared to full universities.

[4] https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/ARES_2017-18.pdf

[5] http://www.businessinsider.com/us-census-median-income-2017-9; https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvard_University_endowment

[7] https://data.chronicle.com/category/sector/2/faculty-salaries/

[8] https://data.chronicle.com/221953/Tusculum-College/faculty-salaries/

[9] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/03/16/survey-finds-increases-faculty-pay-and-significant-gaps-discipline

[10] http://www.thebestschools.org/blog/2013/11/25/10-highest-paid-college-professors-u-s/

[11] http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2017/5/13/tax-forms-2015/

[12] https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/02/how-many-phds-actually-get-to-become-college-professors/273434/

[13] CAW Table 9 & USDOE chart, 2003

[14] http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm

[15] E.g., Katina Rogers, in her “Humanities Unbound” report for the University of Virginia’s Scholarly Communication Institute (URL =< http://katinarogers.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Rogers_SCI_Survey_Report_09AUG13.pdf>) finds that most PhDs find alternative full-time jobs.

[16] Maseri Nerad, Rebecca Aanerud, and Joseph Cerny, “So You Want to Become a Professor? Lessons from the PhDs—Ten Years Later Study,” in Paths to the Professoriate: Stategies for Enriching the Preparation of Future Faculty, ed. Donald Wulff, Ann Austin, and Associates (New York: Josey Bass, 1999), 137-158.